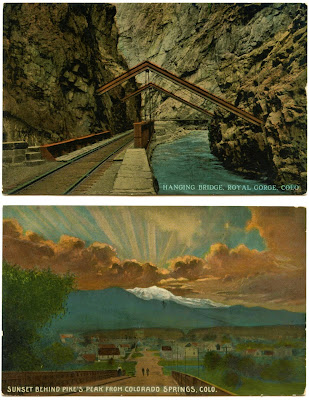

The two trains in these post cards are relatively old. They look like they are

2-6-0 Moguls (according to the Whyte classification system). Moguls were designed to be shorter, and, thus, used in spaces that were limited. They made good yard engines. The top one

certainly looks older than the bottom one. The shapes of the steam and sand

domes, the headlights, the shape of the cabs and the pilots or cow catchers, as they are commonly known, are all

indicators to me of the ages of the engines. Even the dress of the people in the

pictures says to me that the bottom picture is younger. Unfortunately, I could

not see enough detail in the pictures to be able to accurately identify either

locomotive. I can read a "3804" on the tender in the bottom post card; and there

may be a CNR or CPR on the side of the cab, but I cannot confirm this.

The two

post cards you see in this scan are also relatively old. The top could be from

as early as 1907 and the bottom one from as early as 1904. The hint that leads me to that conclusion is held on the backs of the post cards. The two images that you see below are scans of the stamp boxes from the upper right hand corners of the post cards. The one at the top is from the top post card.

The one at the bottom is from the bottom post card. You will notice that both have "AZO" as part of the borders. The differences are in the corners. The top one has 4 diamonds and the bottom one has 4 triangles, all facing up. These differences help us to tell the age of the post cards. The four diamonds were used on AZO paper from 1907 to 1909. The four triangles facing up (later they used two up and two down) are from 1904 to 1918.

What is really neat about these post cards is that they are REAL PHOTO post cards. They were not printed using a printing press. These images are actually photographs. The images were printed on real photo paper that were pre-designed to be mailed after the image was developed. When I look at the images with my very powerful magnifying glass, I do not see a series of dots (as in a printing press image); I see continuous pictures.

The papers used for this process were manufactured by suspending very tiny particles of silver in a gelatin-based emulsion. They were much faster to develop than the earlier versions of REAL PHOTO papers. Their ease of use made this system of photography/post carding extremely popular. People used this system for family pictures, family events, sports events and corporate events - like posing around steam locomotives.